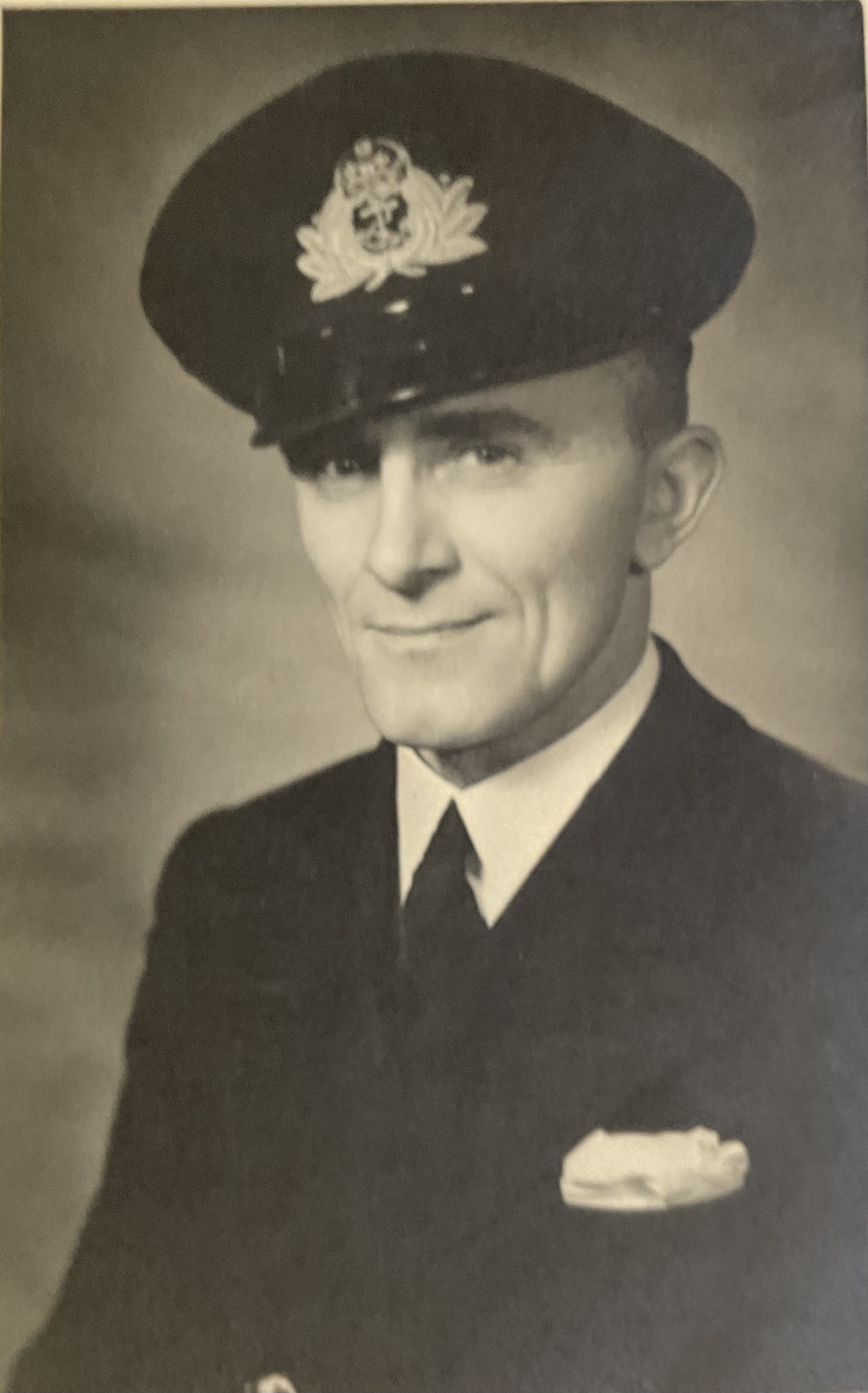

My father, Alan Alfred Browne, enlisted in the RNVR in 1940 and did his initial training at HMS Collingwood, but was then transferred to HMS Vernon as a member of the newly established Instructional Book Production Department.

The Department was apparently initially based in a house on the corner of Southsea Parade and Florence Road, which later became Rose Lodge Nursery School, not far from Gun Wharf and the rest of HMS Vernon in Portsmouth. However, after the bombing raids on 4 August 1940, and the destruction of the Dido Building on 9th March 1941, the Vernon staff were dispersed to several safer locations, with the bulk going to Roedean School, near Brighton Vermom (R). The Book Department were moved to Ryecroft House at Ropley, Hampshire, which had previously belonged to an Admiral Henderson.

My father was billeted at a farm in nearby Ropley Dene, and I was taken to visit the farm one weekend by my mother in late 1940 or early 1941, aged about 2. I had an altercation with a nanny goat who did not like me touching her small kid, and without the goat I might have forgotten this visit.

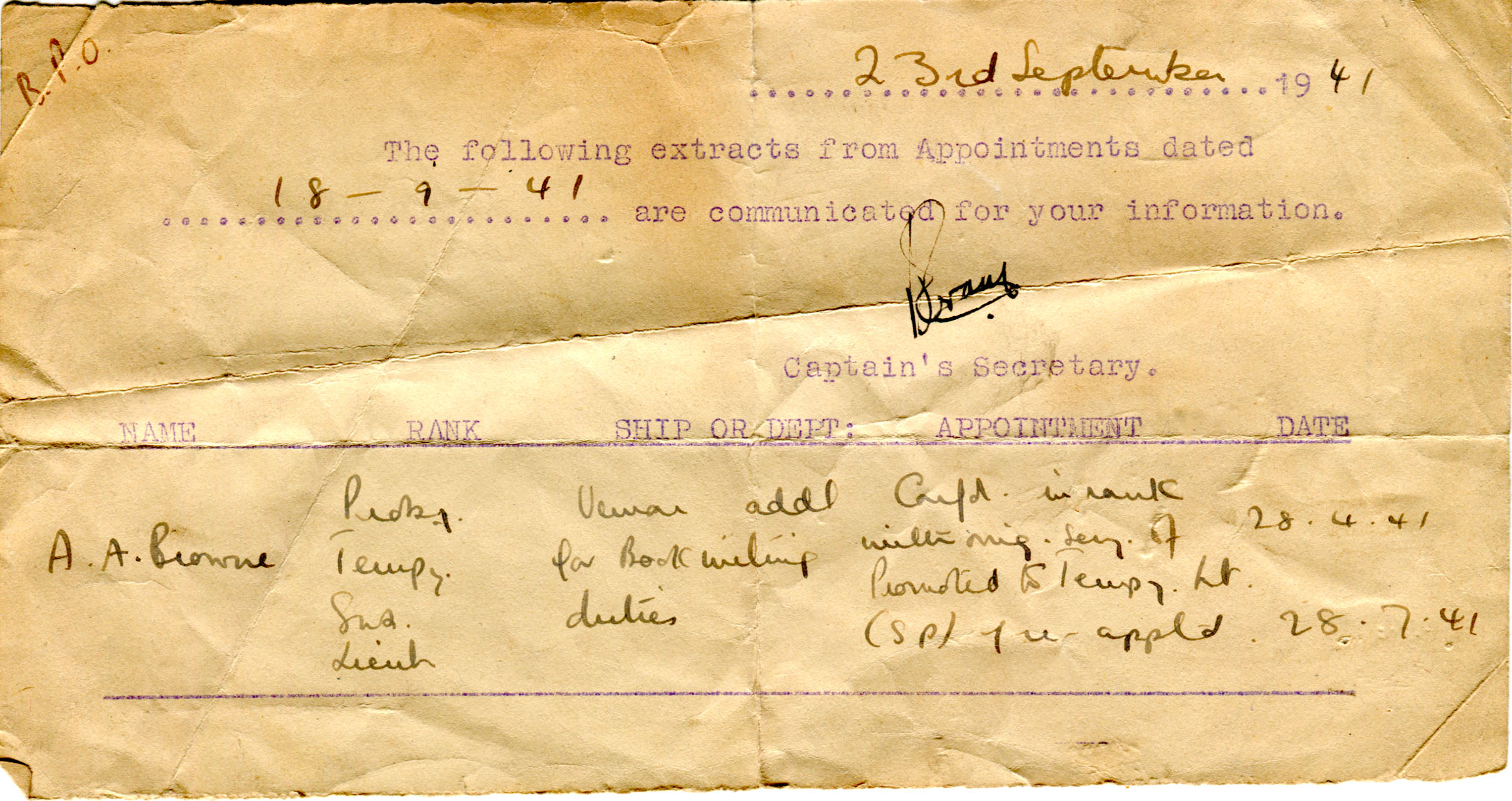

This document shows one of the formal promotion notifications for my father, appointing him as Sub-Lieutenant (Special Branch) R.N.V.R. He was promoted to Lieutenant on 23 July 1941.

I also have a virtual P60 showing his pay, tax and allowances, from which I note that the Navy was allowing £50 pa for my own upkeep. Unfortunately, the document is undated, so it is not clear what rank is being rewarded. Still, it mentions a previous year’s pay for comparison, so I assume it is from at least 1942 and thus refers to the pay for a Lieutenant.

My father had been taught technical drawing at school and wanted to be an engineer but was dissuaded by my grandmother. He was passionate about radio and had built himself a crystal set as a teenager, and he continued to teach himself electronics. He could mend anything from a radio to a clock, or a vacuum cleaner. He was thus largely self-taught, intelligent, and capable of thinking ‘outside the box’, with a knowledge of electronics. As a draughtsman, he could put his hand inside a complex machine and draw what he could feel when he could not see it.

The Instructional Book Publishing Group, which started work in 1941 at its new rural home in Ropley, had its photos taken around October 1941, which in some way served to bond the group together, but also showed its links with the community outside.

Unfortunately, the most important photo, a group shot of the Book Production Group Naval officers, is now lost from my collection, but the officers appear in the group photos 2 and 3.

The new home of the Book Publishing Group at Ryecroft House, Ropley. It had been a comfortable family home, and was large enough to house not only the group but also provide space for printing, collating, binding, and finally arranging distribution of the books.

The entire staff were arranged in front of the house for this picture

This group shot was clearly taken on the same occasion as the previous photo: all the house staff are wearing the same clothes, and, while some members in the second row have changed places, most people are in precisely the same positions, with the WRNS still sitting in the front on two rugs as before.

The rank insignia of the officers are visible in these photos, so it is possible to try to assign names to them using the June 1942 Navy List. This showed that there were eleven officers in the unit: two retired RN Commanders, who had re-enlisted, a retired Lieutenant, who had also re-enlisted, two temporary Lieutenant Commanders (Special Branch) RNVR, and five Temporary Lieutenants (Special Branch) RNVRwith a sixth man still a Temporary Sub-lieutenant (Special Branch) RNVR.

Looking at the garden photograph: In row three, standing, the two Commanders are visible: sixth from the right is Commander H L Welman, a serving officer in the Royal Australian Navy who retired in 1928. He was one of many RAN officers to volunteer at the outbreak of WWII, and he was the first officer to be appointed to a new Instructional Book Production Department. Beside him is Commander V A L Bradyll-Johnson, another retired officer who volunteered to serve in the latest war.

In the second row, seated, extreme left, is an RNVR Sub-Lieutenant, M Bagot. The grey-haired grey-haired Lieutenant RNVR next to him may be Temporary Lieutenant C Sylvester, while Acting Lieutenant N A Citrine, RNVR, who had joined the group in July 1941, is sitting between him and the Army officer. The RN Lieutenant fifth from the left is likely to be Lieutenant T Lancaster, the third retired officer who had re-enlisted.

The RNVR Lieutenant next in line could be either Acting Lieutenant D C Quail, or F W Harvey, who had both joined in October 1941. Next to him is a Lieutenant Commander RNVR who is either H P C Thomas or C E N Clowser, and from his apparent age, I think it may be Clowser, born in 1904. This means that H P C Thomas is missing from the photo.

Second from the right is my father, Lieutenant A A Browne, RNVR, with a fellow Lieutenant RNVR at the end, who is either Lieutenant D C Quail or F W Harvey. In the front row are six WRNS.

The WRNS, with the two Commanders, are still wearing the soft, pudding basin hats, which date the photos to 1941, as in 1942, the hats were changed to a hard top. In the centre front is Leading WRNS Edna Jones - her fouled anchor badge is just visible on her left arm. Although the Navy List of 1941 does not list names of the WRNS, a family member has identified her.

In this picture, the two Commanders are grouped with members of the local Women’s Voluntary Service (WVS), later the Women’s Royal Voluntary Service (WRVS).

One duty of the WVS was to arrange homes for evacuees, and perhaps the local group had been employed in finding billets for the members of the department within an easy travelling distance of Ryecroft, which could not have been easy in this rural area.

Two of the ladies are wearing the official green tweed coats, and the lady on the left is also wearing the official red and yellow striped scarf, while her neighbour has a rank badge on her sleeve. Almost all the others are wearing one of the enamel badges on their left breast denoting their membership of the WVS.

One lady stands out from the group in the front row. She is wearing leather gloves, holding a handbag, and wearing an elegant hat. Was she a member of the local gentry?

The photo also shows that there was another unseen member of the establishment – a ship’s cat. Three of the ladies, including the gloved lady, are holding kittens but the mother is not in evidence. (One lady, who appears in both the department staff Photos, is also cuddling a kitten.) The cat may have already been living in the house and was acquired by the MOD as part of the fittings or as the official rodent catcher.

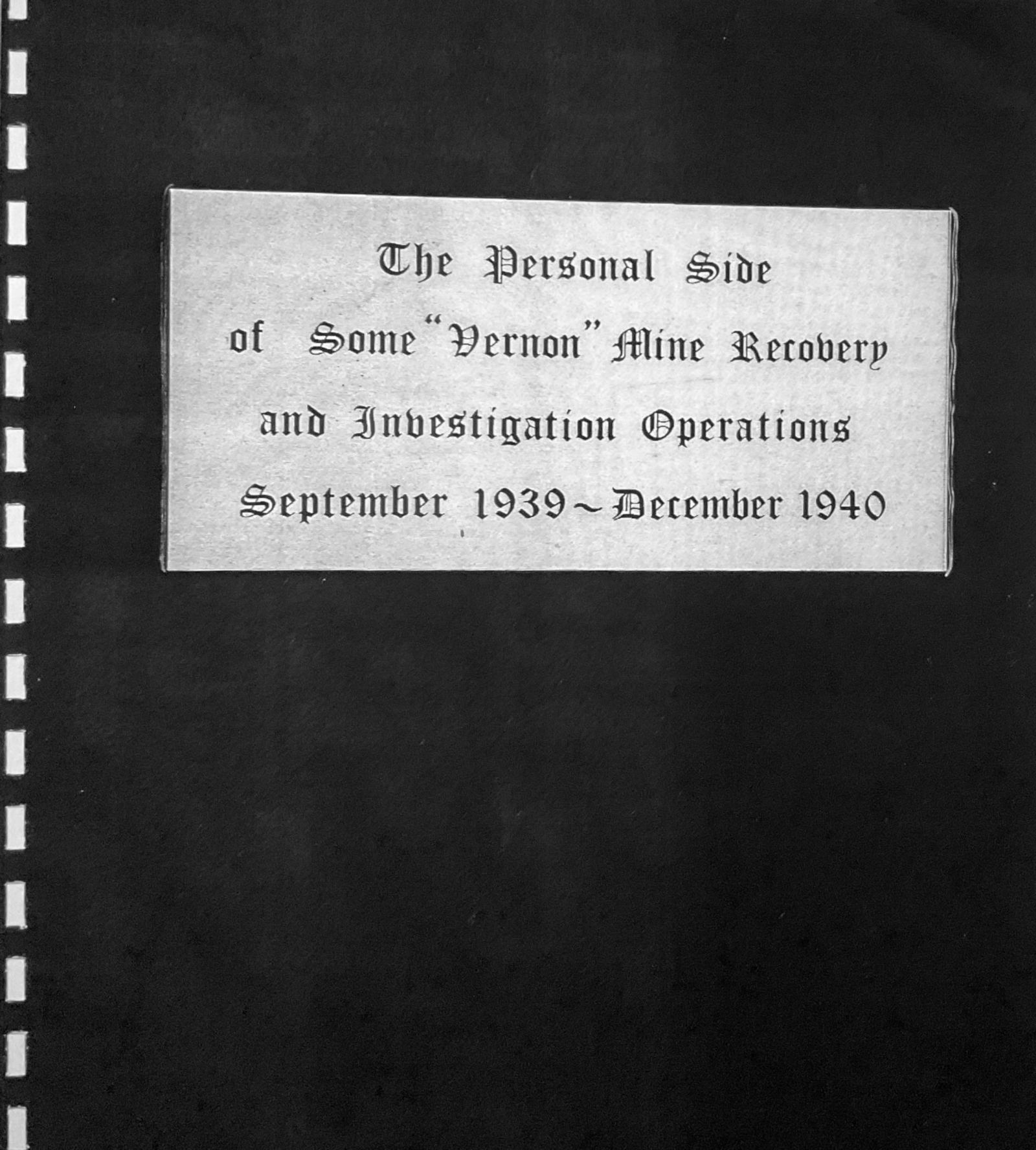

One early book produced for the (M) section of the Vernon based at West Leigh Cottage near Havant, was Vernon Pamphlet no. 370. THis was compiled by Lieutenant G H Goodman, has a preface from Commander G Thistleton Smith, which mentions that just 24 copies of this highly secret book were to be published by the Instructional Book Production Department for distribution. The 77 page Pamphlet was titled The Personal Side of Some “Vernon” Mine Recovery and Investigation Operations, September 1939 – December 1940.

However, due to the sensitivity of the accounts of German mines being found, and the defusing methods detailed in the book, it was to be held securely and not distributed until the end of the war. It included accounts of operations from various members of the group in the initial months of the war. The book is available online in facsimile and was used as source material for many later books, such as “Service Most Silent” by John Frayn Turner.

One name on this distribution list is Lt. Commander C E Clowser, who, as noted above, was a member of the Book Production Department rather than a mine researcher, so perhaps he acted as editor.

At this point, I have a problem, at present unsolved. Rear Admiral Poland, in his history of the Vernon, says on page 293 that the group returned in 1946 to Portsmouth from Ropley, but I know that my father and some, or all, of the rest of the Book Production Department moved to Havant for the last few years of the war.

The base at Ryecroft had one severe disadvantage: it was isolated from the other units of the Vernon at Havant or Roedean. (The Pay Department of the Vernon was also in or near Ropley, and perhaps also at Ryecroft, but were presumably not requiring booklets.)

My father was billeted for several years at 64, Southleigh Road, Warblington, Havant. I don’t think he was alone, as he often mentioned his fellow officers in later years, particularly Citrine and Harvey. I can confirm this move because for the last six months of the war, aged 5 or 6, I was rescued by my father and his kind Warblington hosts from the constant bombing by German rockets over our London house, and I went to live with him. The Chapmans already had three older daughters, and accepted me warmly as just another small daughter. There were no spare bedrooms, so I slept with their eldest daughter, Margaret. During this stay, I even visited my father’s office, and remember that it was like a small staff bedroom in a large house with a beautiful garden, but this can be a description of any of the nearby properties acquired by the Admiralty.

At present, I have no other corroborating evidence, except a later photo I possess in which I am standing outside Warblington church door as one of the bridesmaids to the youngest Chapman daughter in 1949.

The Admiralty had acquired a cluster of local houses after the Portsmouth bombings for sections of the Vernon, and as these are not detailed elsewhere, I will list them, knowing that my father was working from one of them.

Leigh Park House was a vast Victorian Gothic mansion, and was occupied by the Mine Design Department and a huge civilian staff.

.jpg)

Leigh Park House staff.

One valuable amenity to Leigh Park House was the proximity of a large ornamental lake in its park, in which experimental mines could be detonated for testing. It appears that Francis Crick was based at Leigh Park at this time, working as a physicist rather than as a microbiologist of DNA fame. He was interested in magnetic and acoustic mines and designed a new mine effective against German minesweepers. A manual must have been produced by the Book Production Department.

There was a second large house nearby in what is now Staunton Park - West Leigh house – and Emsworth Museum has a photo which they think dates from the early 1950s showing that it was Georgian rather than Victorian, but with an equally large, sprawling footprint. It provided a base for the Trials and Scientific Department of Mines. (As the Department had returned to Portsmouth by this date, I think the photo is actually from the early 1940s rather than the 1950s.)

West Leigh House and staff.

A third, smaller, house nearby, West Leigh Cottage, housed Vernon (M) with Commander G Thistleton-Smith. The text of the classified book on mine detonation was sent from here to the Book Production Department in 1941, and in the second row of the photo from the front, behind the WRNS, may be seen Commander Thistleton-Smith, eighth from the left, with Commander J G D Ouvrey to his left.

Many of the men in this photo were decorated for their extreme bravery in the early months of the war. Their task was to investigate new German mines washed up or dropped by parachute up and down the coast in an effort to blockade English ports. Commander G Thistleton-Smith, for example, received the George Medal, and Commander J Ouvrey was awarded the Distinguished Service Order. Working mainly in pairs, they were required to investigate examples of new German mines, deduce the category of each, survey the fuse as best they could to decide what non-ferrous tools were required to deactivate them and arrange for their manufacture by the Royal Engineers or the National Physical Laboratory. Some mines also contained booby traps, requiring additional assessment and defusing. When made safe the mines were transported back to the Vernon for further research and removal of the explosives. Finally, the results of these successful pioneer operations were disseminated to RMS groups (Rendering Mines Safe) established along the coast and in cities.

A fourth house, East leigh House, lay close by the perimeter of the Park and the Vernon Electrical Department was located here.

Emsworth House was also acquired by the Admiralty, according to the staff at Emsworth Museum, but I have not been able to find out which section was based there, so it could have been a base for the IBPD, if the whole Department moved to Havant.

No image for this property.

Warblington House, located close to the castle and off Pooks Lane, was reportedly used by the Vernon Finance Department, according to Havant Museum. However, I have not found any photos or other references to support this.

I believe that the Instructional Book Production Department were producing manuals for various sections of Vernon, and I have already mentioned the secret book produced for (M) division, and there appears to be good reason to transfer my father, a group of officers, or all the staff from Ropley to an office in close proximity to the cluster of houses noted above.

In the later months of 1941 and early 1942, Vernon (M) found it necessary to train over two thousand officers and men in recognising German mine types, in knowing how they should be treated and defused. They were then provided with the right tools, which needed, above all, to be non-ferrous. This means that although it was imperative to prevent the Germans from knowing that their mines had been understood, it would also have been necessary to produce training pamphlets on each type of mine.

In producing this material, the physical distance of the Book Production Department from Havant would have been an operational disadvantage. At the outset, only a handful of men at West Leigh Cottage, like Commander Ouvrey, knew the secrets of these devices, including possible booby traps, and they would have had to supervise the technical drawings in minute detail, provide the accompanying photographs, and closely scrutinise the text of the pamphlets. Any error in these diagrams could have cost lives. However, this small group of experts were also constantly touring the coast as each alarm call was received, noting that yet another unidentified object had been found either on land, on the sea surface, or at a depth of water, so their time and energy were already at full stretch.

In addition, the mine development scientists in Leigh House would have also needed to provide training booklets on the British mines they were developing, including their safe handling and the means of defusing them in an emergency. Methods of degaussing the ships, or developing safe trawl methods, etc., would all have required similar detailed instruction methods in booklets.

Further, the Electrical Department at East Leigh House nearby was working on naval uses of radar, ASDIC, and other systems for which maintenance and operating manuals were required, and which needed writers and technical artists who understood circuitry, as did my father. Again, at each stage of production, the technical authors would need their work checked by a member of the Electrical Department and repeated visits to or from Ropley wasted everybody’s time.

My father had presumably signed the Official Secrets Act, which prevented him from telling us about his current work, but he did reveal several projects later. The first, and perhaps the one that excited us most, was to help write the handbooks for the use and maintenance of radar equipment, and the close proximity of the Electrical Department at East Leigh House makes this a feasible possibility. Mine production was also a frequent dinner table topic of conversation for years to come.

The other project, which my father mentioned, occupied him in 1946 after his return to Portsmouth, and this was not for Mines or the Electrical department. The task was to write a handbook on the use and maintenance of some large Naval guns guarding the channel, and based for safety inside a cliff, but I don’t know the location. It was his final task with the Vernon, and he found the power and size of the guns inspiring.

It is perhaps worth commenting on the production methods used by the group, since they may be unfamiliar to generations with the facilities of photocopiers, and computers. Images from the 1941 book by Lieutenant G H Goodman, at (M) reproduced above, give useful as clues to methods available, at least earlier in the war.

The title on the cover has an unusual, nineteenth-century-styled Gothic typeface, not available on a typewriter, and the book appears to be ring-bound. The title page features a crest and lettering that are not from a typewriter. Available at this time were metal stencils which could be used to reproduce lettering of larger size than that of a typewriter and in different typefaces, or skilled calligraphers could have been used to produce this cover. In addition, small printing sets were also available to typeset small projects like labels for the cover and the title page.

The rest of the pages are typewritten, not typeset, and were typed on one of the Gestetner-type stencils. This meant that the text could be reproduced in bulk when the stencil was mounted on a metal drum, and ink was forced through the holes cut in the typed stencil onto a sheet of paper. It was a cheap way of mass-producing documents, popular for newsletters and company documents. Mistakes in typing could be corrected by a waxy liquid, such as the substance later sold under the brand name of “Tipex”. A typo correction is visible on the last page of the book, for example.

The illustrations are photographs individually glued into the books. A recent example of the book which is being auctioned shows that the glue had failed at a later date and been replaced by Sellotape, which raises the problem of what kind of glue was being used in 1942. Hot glue made from animal bones would not be suitable for paper, which leaves three alternatives: plain wheat flour and water, corn flour and water forming a dextrin glue, and caseine glue made of milk protein. Caseine took about 2-4 hours to set, and milk was in short supply in 1942, so it is more likely that dextrin or wheat flour and water paste were used.

Many of the books produced were working handbooks on the use and maintenance of equipment, with text, photographs, and diagrams. The technical images were reproduced as “blueprints” – literally blue - by which linen or paper was impregnated with ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide to produce a cyanotype. When a tracing of the diagram was placed on the surface and exposed to light, a negative photographic image was produced, consisting of white lines on a blue background and it required only water to develop and fix the image. From these negative multiple copies could be produced.

I know this process was being used, and used on linen rather than paper, because occasionally, when an image became obsolete, it was boiled to remove the chemicals and starch, leaving behind a useful piece of cloth. My mother was sometimes presented with one of these valuable remnants, which could be used for dressmaking or household articles. With the shortage of cloth and clothing in wartime conditions, it was a welcome piece of recycling for something that would otherwise have gone to waste.

I am left with the major problem of the change of venue in writing this article, but I have no doubt of the move of my father alone, or part, or all, of the Book Publishing Department to a location which was within easy cycling distance of Southleigh Road in Havant. (All the buildings I have listed qualify as being in easy reach of my father’s billet.) I hope that another family member may come forward with corroborative information and perhaps can identify the house used for the work.

I also regret the loss of the officers’ photo – it still exists in my memory, but the technology does not yet exist to download my mental image.

I have been helped in this account by various contributors to the Project Vernon Facebook group including invaluable guidance from Rob Hoole, the webmaster, Carole Oldham of the Ropley History Group, the staff at Emsworth Museum, the staff of The Spring Arts and Heritage Centre Museum, Havant, Beccy Humphries for information on Edna Jones, and my friend, Van Woodward. with her knowledge of the WRNS and the Vernon.

Rosalind Thomas, MA, August 2025In memory of my father, Alan Alfred Browne, 1903-1985

© 1999-2026 The Royal Navy Research Archive All Rights Reserved Powered by W3,CSS

Because of the later celebrity of Lieutenant Citrine and his father, I have been able to write a short biography for him, but have not been able to trace many of the former and later lives of most of the other group members.

My father often mentioned Lieutenant Citrine, whose father, McLennan Citrine, was at this time Secretary of the TUC, who, according to Wikipedia, until 1946, “he helped create a far more coherent and effective union movement.” Walter was also President of the International Federation of Trade Unions until 1945, and joint Secretary of the TUC/Labour Party National Joint Council. Crucially for his work, he was born into a working-class family in Liverpool, leaving school at 16, and this lower-class background influenced his life, work and attitude to life. He first worked in a flour mill, but taught himself electrical theory, economics, and accountancy. He joined the Electrical Trade Union in 1911 and became a leading member of the union.

Knighted in 1935, Sir Walter Citrine was granted a peerage by the new post-war Labour Government in 1946, taking the title First Baron Citrine of Wembley. In the same year, he retired from the TUC to become a member of the National Coal Board for a year, working to improve the welfare of miners. He took his title, Baron Citrine of Wembley, from his many years living with his family in Wembley Park. He attended the House of Lords and continued his other work for unionism.

His eldest son, Norman Citrine, born in 1914, was clearly influenced by his father: he became a lawyer, not by attending university, but by working his way up through chambers, and shared his father’s interest in electronics. This developed an ability to work things out for himself rather than learning them from others. Norman became the Legal Adviser to the TUC in 1946, thus continuing the work of his father. When Sir Walter died in 1983, Norman succeeded him as the 2nd Baron Citrine. He also attended the House of Lords until his death in March 1997.

There is a photo of Norman Arthur Citrine taken in 1952, held in the National Portrait Gallery online collection, from which it is possible to identify him in the group photo taken outside Ryecroft House as third from the left in the first seated row, behind the WRNS.

Comments (1)

A remarkably detailed account, the result I suspect of many hours of research. It sheds light on what for most of us a little known aspect of Vernon's history and the work of a few more unsung heroes quietly getting on with the job.