Mobile Naval Air Base No. IV

Assembly and commissioning in the UK

Personnel and equipment for Mobile Naval Air Base No. IV began to assemble assemble on November 15th 1944 at

Royal Naval Air Station Ludham, Norfolk, the headquarters of the Mobile Naval Airfields Organisation (MNAO). The unit was to form as a type A (Small) MONAB tasked with supporting up to 50 aircraft and was allocated the following maintenance components:

Mobile Maintenance unit No. 3 supporting Avenger Mk. I & II, Firefly Mk. I, Seafire Mk. III & L.III

Maintenance Servicing unit No. 5 supporting Corsair Mk. II & IV

Maintenance Servicing unit No. 6 supporting Hellcat Mk. I & II

Maintenance Annex No. 1 supported aircraft type not known

Additional components added after arrival in the Pacific theatre in response to a change in roles:

Maintenance Storage & Reserve unit No. 1* Avenger Mk. I & II, Corsair Mk. II & IV, Hellcat Mk. I & II.

Maintenance Storage & Reserve unit No. 4 Avenger Mk. I & II, Corsair Mk. II & IV, Hellcat Mk. I & II

Maintenance Storage & Reserve unit No. 6 Firefly Mk. I, Seafire Mk. III & L.III, Sea Otter

Mobile Air Torpedo Maintenance Unit No. 7 * Formed the forward Aircraft Pool

on Pityilu Island under MONAB 4 control.

This division of the complement made kitting up, checking of lists, and arranging short maintenance courses, and ultimately embarkation, unnecessarily complicated. To further compound an already complicated restructuring of the unit's assembly and formation period it was found that many of the ratings drafted were unfamiliar with the several types of aircraft which it was intended that MONAB II should handle; the formation time table made no allowance for rating familiarisation, unit sailing dates were pre-set so training outside of that set out in the formation programme was sacrificed. In addition to unprepared technical ratings, no adequate writer staff were drafted, ratings received were inexperienced; of three supplied for the workshop element, only one could type with any speed or accuracy.

The severe winter of 1944 was to compound the strain of the day-to-day routines of the assembling units, things inevitably slowed down; ratings were forced to queue for hours in rain, mud and snow for personal kit issues. Ludham was not an ideal base for the formation of units like MONABs; it was a dispersed airfield where all of the facilities were located around the outer edges of the base. The majority of the airfield was open grass, this was used for all manner of purposes from vehicle parks to large areas of tented accommodation erected to house the personnel of the assembling MONAB units; all became a quagmire. The severe winter of 1944 was to compound the strain of the day-to-day routines of the assembling units, things inevitably slowed down; ratings were forced to queue for hours in rain, mud and snow for personal kit issues. Ludham was not an ideal base for the formation of units like MONABs; it was a dispersed airfield where all of the facilities were located around the outer edges of the base. The majority of the airfield was open grass, this was used for all manner of purposes from vehicle parks to large areas of tented accommodation erected to house the personnel of the assembling MONAB units; all became a quagmire.

MONAB IV commissioned as an independent command on New Year's Day 1945 bearing the ship's name HMS ‘NABARON', Captain A.N.C. Bingley in command.

Despatch overseas

By mid-January the unit was ready for despatch overseas; all of the mobile units planned had been allocated to the support of the new British Pacific Fleet (BPF) which was to begin operations in the South Western Pacific in early 1945. Australia was to be the rear echelon area for the fleet [ the first 8 mobile units were despatched to Australia to await allocation of an operating location, a number of the MONABs were to be installed there. The unit's personnel, Stores and equipment were transported to Liverpool for embarkation on January 16th 1945. The personnel embarked in the troopship DOMINION MONARCH, stores and equipment in the SS CLAN MACAULAY; both sailed with convoy UC.53A on the 19th.

After calling at New York the DOMINION MONARCH passed through the Panama Canal to enter the Pacific, and arrived in Sydney, Australia on February 21st, the personnel were disembarked to HMS GOLDEN HIND, RN Barracks at Warwick Farm Race Course, to await the allocation of an operating base. Departmental officers lived in Sydney and were thus able to liaise directly with the staff of the Flag Officer Naval Air Stations (Australia).

The planning staff of the BPF headquarters decided that MONAB IV would become the first unit to be established in the forward area, its operational base was to be at Ponam, in the Admiralty Islands where US Navy airfield facilities had been loaned from the Americans. To this end the CLAN MACAULAY, still on passage, was diverted to the fleet anchorage at Manus, Admiralty Islands in preparation for occupying Ponam airfield.

Leapfrogging to victory - the first stage: The conceit of the Mobile Airfields was simple, as the Fleet operating area moved further forward MONABs would be established at suitable island locations to provide the shore based forward area support, once the operating area moved forward again another MONAB would ‘leap-frog’ the last one installed so forming a chain of bases between the forward area and the intermediate base at Manus. MONAB IV was to be the first link in this island chain. The decision to install MONAB IV in the forward area meant that in addition to its primary role of supporting disembarked front-line squadrons, it was also tasked with providing reserve aircraft storage. Reserve airframes would be issued to the fleet as required or ferried forward in replenishment carriers to provide replacements at sea as part of the Fleet Train, the support ships of the BPF. In order to provide the storage facility an additional component was added to the unit’s compliment; Maintenance Storage & Repair unit no. 4 (MSR 4) was transferred from the strength of MONAB II at RNAS Bankstown, Sydney.

The vehicles, equipment and a small advance party of MSR 4 were ferried to Ponam on the maintenance carrier HMS UNICORN which sailed for Manus with the BPF, arriving on March 7th; unloading began on the 8th. Three months Victualling stores were also delivered on the 8th by the Victualling Store Issue Ship (VSIS) FORT EDMONTON. Five days later the CLAN MACAULAY arrived at Manus on March 13th with the stores and equipment of MONAB IV.

The advance party, of 6 Officers and 57 ratings, together with the remaining elements of MSR4 arrived at Ponam on the 15th on board the escort carrier SPEAKER to begin unloading the CLAN MACAULAY. The first aircraft on the station were six Corsairs disembarked from UNICORN with MSR 4; initially the only Pilot was the Lieutenant Commander (Flying) who arrived with the advance party and all test flying of the aircraft, and routine trips in the station's Stinson Reliant 'runabout' had all to be carried out by him until two dedicated test pilots, RNVR Sub-Lieutenants P. J. Hyde and J. E. Jones, arrived on April 3rd. There was no need for test pilots in the unit’s original tasking sand none had been available to travel from Sydney with either the advance party or the main body.

The main party arrived at Ponam on the 25th on board the Landing Ship Infantry (LSI(L)) EMPIRE ARQUEBUS, by this time all domestic services were functioning. The next eight days were spent in the installing of equipment and organising the setting up of the ship (RN shore establishments are still classed as ships). Considerable help was received from the US Navy Seabee (Construction Battalion) maintenance unit, which was billeted on Ponam, and in the early days their aid was invaluable. While in Sydney the senior officers had managed to acquire some domestic refrigerators and Wiles Mobile Galleys to replace the antiquated and unsuitable types provided in the U.K.; as it transpired no mobile galleys were actually needed since Ponam was a fully equipped airfield, however the Wiles Mobile Galley was considered to be ideal for a forward operating MONAB.

Prior to the arrival of MONAB IV the forward area aviation support comprised of lodger facilities granted at the US Naval Air Station on Pityilu Island, 22 miles east of Ponam. The Maintenance Carrier UNICORN was to remain at the fleet anchorage and eventually put ashore a small test flight to Pityilu for maintenance test flying of airframes that had been repaired onboard. The only squadron use of Pityilu airstrip was made on March 15th when the BPF carriers INDOMITABLE, VICTORIOUS, and INDEFATIGABLE flew ashore a proportion of their Squadrons to Pityilu Island after two days of intensive flying training at sea; arrangements had been made with US authorities for this to be done, the carriers landing the necessary personnel, etc. They had all re-embarked by the 18th when the BPF sailed from Manus for Ulithi Atoll to begin strike operations.

Commissioned at RNAS Ponam, Admiralty Islands

The former U.S. Naval Airfield Ponam was commissioned as HMS NABARON, Royal Naval Air Station Ponam on April 2nd 1945.

RNAS Ponam, a former US Naval Air Station built on a small coral island, looking south to north.

As the unit began to settle in it soon became apparent that the MONAB was not equipped, and in some areas not adequately manned, for the tasks it was expected to perform. Another major short coming, on the flying side, was parachutes, 3 Pilot type Parachutes were supposed to be included in the main stores, these had not been supplied even by the time the Pilot strength had been increased to four, and consequently all flying had to be centred round three borrowed parachutes. The maintenance of parachutes also does not seem to have been considered by the Admiralty, no tables or even packing sheets were provided; in a damp and hot climate like those experienced in the tropics it is hard to speculate on the fate of any parachutes not receiving regular maintenance, thankfully a complete parachute servicing installation, equipped with dehumidifying plant, had been erected by the U.S. Navy. With the arrival of Squadrons, it became apparent that additional vehicles, either 15 Cwt type and/or Jeeps, should have been allowed for as squadron transport. Although 4 Jeeps were laid down as part of the complement of the ''F" component, only two were received before leaving the UK. The Crash Tenders originally supplied were found to be obsolete and useless. These and other shortcomings were represented to Flag Officer Naval Air Pacific (FONAP) and two new crash tenders were eventually supplied.

The absence of any crane able to lift any type of naval aircraft was another serious omission, luckily the Seabee maintenance unit came to NABARON's rescue. From the time MONAB IV arrived until the beginning of September maintenance of the camp electrical services were carried out in conjunction with the Seabee unit; NABARON personnel did the majority of the work since the American unit had only one electrical rating. Work carried out included general maintenance of galley electrical machinery, the telephone system and lighting system, rewiring of old installations and erection of new wiring for new requirements, replacement of poles, and the re-organisation followed by the maintenance of the runway lighting system. This endless task kept a party of one Chief Electrical Artificer, one Petty Officer Wireman, one Leading Wireman and six other ratings continuously occupied.

On the 30th of April HMS NABARON commenced a programme of training for aircrews, two Avenger aircraft together with four spare crews disembarking from the ferry carrier HMS FENCER. This was to be the start of the build-up of the reserve aircraft to be held at the station; by the end of May 40 reserve airframes had been received from the ferry carriers. There were no aircraft issues made during this period.

First squadrons arrive: The escort carrier BEGUM arrived off the island on May 28th to deliver the first resident squadrons, 721 Fleet Requirements unit (FRU) equipped with 6 Vengeance TT.IV target tugs and 'B' Flight of 1701 Air Sea Rescue (ASR) squadron equipped with 4 Sea otter amphibians. No. 721 squadron was to provide aircraft to act as targets for fighter interceptions and lowing drogues for air to air firings to exercise with the ships of the BPF and squadrons ashore at Ponam. 1701 was to begin operations from Ponam in support of carriers working up in the area. Also arriving on the station on the 28th were detachments of 6 aircraft each from 801 & 880 (Seafire) squadrons, and 828 (Avenger) squadron's 15 aircraft on the 29th, all from the Fleet Carrier HMS IMPLACABLE which was completing her work up period.

The arrival of these aircraft marked the start of a six-week training period, during this time Ponam was to be used for Aerodrome Dummy Deck Landing (ADDL) training. 801 & 880 Squadron detachments re-embarked on the 31st; they were replaced on the same day, by 1843 (Corsair) Squadron which disembarked from HMS ARBITER with 24 aircraft, and 885 (Hellcat) Squadron from HMS RULER bringing 20 aircraft. By this time the Station Flight of Stinston Reliant aircraft proved to be an invaluable asset, being continuously employed carrying Personnel, light Stores and correspondence up and down the reef.

Another MSR arrives: June was a very busy month. A second Maintenance Storage & Repair unit, MSR 6, arrived on June 1st on the escort carrier ARBITER; this additional unit, equipped to service Firefly I, Seafire III & L.III and Sea Otter aircraft increased the stations reserve capacity to 100 aircraft. MSR 6 was initially attached to MONAB II at RNAS Bankstown, Sydney after its arrival in Australia on April 9th before embarking in ARBITER on May 18th for passage to Ponam. The same day saw the arrival of the VSIS FORT ALABAMA with a further three months stores. ADDLs continued with Seafire aircraft of both 801 and 880 squadrons and 1771 squadrons Fireflies being frequent visitors to the station. The latter disembarked a detachment of 7 aircraft on the 9th, the same day 6 Avengers of 828 re-joined IMPLACABLE. The remaining 9 aircraft and the detachment from 1771 re-joined the ship on the 12th. The Hellcats of 885 re-joined RULER on the 17th, only to disembark a detachment of 12 two days later to spend a week of intensive ADDLs and live firing; a few Corsairs were attached to the Squadron during this period, re-embarking in RULER on the 28th. The Corsairs of 1843 re-joined ARBITER on June 25th.

The RN Forward Aircraft Pool established on Pityilu Island: The planning staff of the BPF headquarters decided that MONAB IV was to be joined in the Admiralty Islands by a new, but separate unit, the RN Forward Aircraft Pool (FAP); originally it had been hoped that this unit would be located at Samar in the Philippines, however operational difficulties and a lack of suitable facilities becoming available from the Americans led to these plans being changed. The Lodger facilities secured on U.S. Naval Air Station Pityilu provided a compromise solution, the airfield was still in use by the US Navy as an Air Maintenance Depot. The RN FAP sailed from Sydney onboard HMS PIONEER on June 16th. This unit was to be a Forward Reserve Aircraft Depot, the main component being MSR 1 which was detached from MONAB I at Nowra, New South Wales on June 7th. PIONEER disembarked the FAP to Pityilu Island on June 21st, when it became attached to MONAB IV for administration purposes. The facility was already used by the Fleet Train aircraft maintenance and repair ships UNICORN, and later PIONEER, for maintenance test flying of airframes that had been repaired onboard.

During June the numbers accommodated on the island were at their highest, in addition to the squadrons ashore recreational parties from the Fleet were also accommodated for periods of 48 hours. In general, the organisation coped with these additional numbers, except for the extra strain on the Wardroom Cooks and Stewards. MONAB IV's complement, including the 2 MSR units, totalled around 785 men, but it was further tasked to provide accommodation for up to a further 930 officers and men from both resident and disembarked squadrons. At its maximum capacity HMS NABARON could be home to 1700 men; overflow accommodation for squadron personnel was provided in the form of native style reed huts along the edges of the lagoon, these were found to be more than adequate for temporary housing. The chief Malariologist on BPF headquarters Staff visited the station to assess the unit’s tropical hygiene and inspect the work of Mobile Malarial Hygiene Unit No.5. This specialist medical unit had been attached to MONAB IV because the Admiralty Islands was an active Malaria region where the disease was transmitted by mosquitoes. He reported favourably on the state of the island from the Health and Hygiene point of view. During the month of June Ponam received 72 reserve aircraft delivered by ferry carriers, the station issued 44 replacements.

There were two serious accidents at Ponam, both during June; one involved a Vengeance Target Tug of 721 FRU, the other a Seafire of 880 squadron. On June 12th, a Vengeance target tug (HB546) experienced control problems on the take-off run, it is believed that either the rudder or one of the ailerons locked causing the aircraft to swing to port. The aircraft crossed the airfield boundary and entered the lagoon. The aircraft turned over on impact with the water and quickly sank in 15 feet of water. Onlookers, including men of MSR 6 ran to the spot where the aircraft had entered the lagoon, several diving in to attempt a rescue the pilot Lt. H Kirby RNVR who survived. As a result of this incident all Vengeance target tugs were grounded until the fault could be identified and rectified.

The second incident was more serious, Sub-Lt Peter Record RNVR of 880 squadron was killed on June 20th when his Seafire L.III (PP957) hit radio masts on approach to a final landing after completing a set of ADDLs. The layout of the Ponam runway was not suited to the landing approach methods required for landing on board carriers so a modified approach was used for ADDLs which involved landing halfway down the runway. This modification worked fine for the ADDLs but was not reinforced by the tower when landing instructions were given at the end of the practice session. Sub-Lt Record reverted to a normal carrier approach in order to achieve the maximum possible landing run and turned into the radio mast near the end of the runway. The Seafire overturned as it hit the runway, pinning the pilot in the cockpit. Onlookers watching the ADDLs rushed up and attempted to extract the pilot by lifting the aircraft's tail high in the air, the pilot had hit the gun sight and had been knocked unconscious, and was unable to get out. Before anyone could get in to pull him out the whole aircraft went up in flames, engulfing those nearby and causing them to drop the tail back on the runway. Moments later the fire tender arrived, however because life would have been impossible in the heavy fireproof, asbestos suits its crew were dressed in bathing shorts and could not enter the flames straight away. The C02 extinguishers had difficulty in dousing the flames sufficiently for the pilot to be dragged clear immediately, finally a crane arrived, and a strop was slid under the tail to lift it high enough to pull him clear. Sub Lt Record was evacuated to the sickbay, but he died from his injuries several hours later. He was buried at sea off Ponam from the deck of a modified aircraft lighter. The occasion was marred by the discovery that the unit's bugler, drafted as such to HMS NABARON, was unable to sound off either the Last Post or Reveille.

A few days after 880 squadron had arrived, someone found a dead Japanese soldier trapped between rocks close by the 'bathing beach', where he had been since the Island was recaptured in late spring of the year before. The 'bathing beach' was at a little bay along the side of the lagoon where either the Japanese, or the Americans, had formed a deep pool in the coral using explosives. Those who used it found it to be only slightly cooler in the lagoon than ashore in the shade, the water temperature was about 90°F (32°C), hot enough for a warm bath.

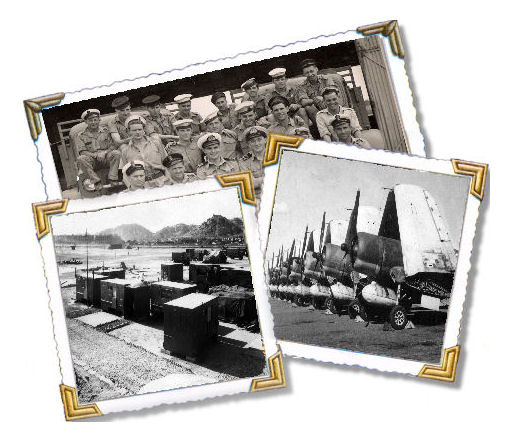

RNAS Ponam aircraft park and maintenance area; there are 17 Vengeance target tugs, 4 Sea Otters & 14 Hellcats in the park, in the maintenance area next to the two Dorland hangars are 3 Reliant communications aircraft and 2 more Hellcats. A single Corsair is parked in the distance. The camp buildings can be seen in the tree line.

July brought Mobile Air Torpedo Maintenance Unit (MATMU) No. 7; this unit arrived on July 6th on board the CLAN CHATTAN having been transferred from MONAB V at RNAS Jervis Bay to bolster the unit’s ordnance facilities. Further provisions were delivered by the VSIS FORT DUNVEGAN on the 15th. On the 18th PIONEER delivered air stores and aircraft lighters to supplement the inadequate supply that arrived with the unit. On July 4th Captain Bingley had been taken ill, and as he showed no improvement, he was flown back to Australia for treatment at R.N. Hospital, Herne Bay, Sydney, on July 17th; Commander. W.S. Thomas, D.S.O., temporarily assumed command.

Further visitors from FONAP’s Staff arrived during July; Commander (A) Wilson and Staff Medical Officer, Surgeon Captain MacDowell, arrived on the 18th. Commander Wilson developed mumps on the last day of his visit and remained at Ponam for a further two weeks until he had recovered. Both these visitors were able to stay long enough to appreciate what living conditions on the station were really like and the recommendations made by them on their return to Australia produced quick results in respect of outstanding commanding officer's reports. UNICORN collected damaged airframes for repair on the 31st at the end of a month were only 6 reserve aircraft were received on the station, but issues were up, at 53.

FONAP visits: On August 1st the Flag Officer Naval Air Stations (Pacific), Rear-Admiral R. H. Portal, C.B., D.S.C. together with Commodore Air Train, Commodore H. S. Murray-Smith, the Staff Air Engineering Officer and Flag Lieutenant arrived on the station. The visitors carried out an inspection tour of the facilities at Ponam, returning to Sydney the next day. The supply of fresh fruit and vegetables by air and the provision of Leave planes to Sydney were discussed and both services were started shortly after FONAP's return to Australia. Rear Admiral Fleet Train (RAFT), Rear Admiral D. B. Fisher, CB, CBE, arrived at Ponam on board the Destroyer Depot Ship MONTCLARE on the 8th to assess the supply arrangements for replacement airframes for use by the replenishment carriers of the Fleet Train; he departed two days later. The opportunity for some recreational activities presented itself; there was a great deal of inter-ship sporting activity and everybody enjoyed the visit. Further stores were disembarked from the ferry carrier CHASER on August 12th, it was intended that she should remain at Ponam to do Deck Landing Training with the reserve first-line crews, but she was required for another commitment and this had to be cancelled.

Victory over Japan and the rundown to closure

The first leave plane to be authorised since the unit's arrival at Ponam departed for Sydney on August 15th, a few hours before the men on Ponam heard the official news of the cessation of hostilities with Japan. Victory over Japan (V-J) Day was celebrated on Ponam the following day.

Although the war was officially over work continued at Ponam as usual, two days after the celebrations of V-J Day SLINGER arrived to collect damaged aircraft for transport to TAMY I at Archerfield, Brisbane, and 1841(Corsair) Squadron disembarked from FORMIDABLE, re-embarking the next day. On the 23rd 12 of 1850 (Corsair) Squadron's aircraft disembarked from HMS VENGEANCE in advance of the ship’s arrival. VENGEANCE arrived at the fleet anchorage at Manus on the 28th and disembarked 6 of 812 (Barracuda) Squadron’s aircraft to Ponam; additionally, 52 Officers & 43 ratings came ashore for short R & R.

A new Commanding Officer arrives: Captain C.J. Blake arrived on August 30th to assume command of MONAB IV, Captain Bingley being unfit to return to duty. Captain Blake had orders to place RNAS Ponam on one month's notice to close down; the Forward Aircraft Pool at Pityilu was to be closed by mid-September. The 812 Squadron detachment and R & R party re-embarked in VENGEANCE. Issues and receipts for August were 48 reserve aircraft received, and 28 replacements issued.

During September preliminary preparations for closing down RNAS Ponam and the RN FAP got underway. All stocks of reserve aircraft held on Pityilu were flown to Ponam; during its time in operation the FAP had handled the reception or embarkation of 348 aircraft, only one being damaged in the process. UNICORN evacuated the FAP on September 17th for passage to Australia. Every opportunity was taken to embark aircraft and stores in ships returning to Australia and a definite evacuation programme had been made out for October. It was expected that by the end of October that the Station would have shut down and all personnel, stores and equipment would have left. A small rear-guard party would be left at Ponam to hand over the loaned American equipment to the US Navy.

A new, and unforeseen, equipment problem arose on September 19th when the first attempt at lifting a Barracuda onto an aircraft lighter threw up a major snag; the American 'A' Frame, used with great success for this purpose, was found not to have sufficient height to lift a Barracuda, eight of these aircraft were at Ponam (ex Pityilu), for transfer by lighter to ship. The Barracuda was a new aircraft in the pacific theatre; they equipped the four new light-Fleet Carriers GLORY, COLOSSUS, VENERABLE, and VENGEANCE, which joined the BPF in mid-August. MONAB IV was not designed to support these aircraft, so unless a suitable crane could be found (one had been requested on several occasions), improvised methods of slinging would have to be devised, a situation which was regarded as less than satisfactory.

The first MONAB components are evacuated: The personnel of MSR 6 were embarked in the escort carrier VINDEX on September 26th, she had arrived form Java carrying hundreds of allied ex-prisoners of war including some women internees for passage to Sydney. The Boom Carrier HMS FERNMOOR arrived the 30th to take on board surplus naval and air stores; she was to remain until October 6th when she sailed shortly after dawn. During the month of September Ponam’s issues and receipts were; Received 45 reserve aircraft issued 52.

October was to be a busy month spent de-storing ship and despatching equipment to Australia. The escort carrier REAPER arrived at teatime on the 3rd to embark 'B' Flt of 1701 Squadron for passage to MONAB VIII (HMS NABCATCHER) at Kai Tak, Hong Kong; the squadron was never called upon to effect an air sea rescue during it's time at Ponam. UNICORN arrived late in the afternoon of October 6th to embark MSR 4 for return to Australia. The morning of the 7th saw the fast minelayer ARIADNE arrive to embark an advance party of officers for passage to Sydney, sailing at 17:00. UNICORN sailed at lunch time on October 9th, 721 Squadron having embarked during the morning. She was to be replaced later the same day by the SS EMPIRE CHARMAIN, which arrived to take on board the vehicles of MATMU 7; she sailed for Sydney on the 16th.

The next 9 days were spent packing the remaining stores, clearing up the station before final departure; UNICORN arrived back at Ponam on the 24th to begin embarking the remaining stores and personnel. CHASER arrived on October 30th to load MMHU 5, two refrigerators and two walrus aircraft. UNICORN and CHASER sailed for Australia on October 31st.

Paying Off

UNICORN arrived at Sydney on November 6th and the next two days were spent unloading stores and equipment onto the jetty for transport to GOLDEN HIND. On the 9th The personnel of MONAB IV embarked in the escort carrier SLINGER, anchored in Sydney harbour, she sailed at 14:00 the next day for passage to the UK; unknown to many of the ship's company HMS NABARON, RNAS Ponam was officially paid off at the same time, the station returning to U.S. Navy control. SLINGER docked at Devonport on Christmas Day, 1945.

HMS 'NABARON'

Function

The support of disembarked front line Squadrons .

The provision of reserve aircraft storage.

721 Fleet Requirements Unit.

1701 Air Sea Rescue squadron 'B' Flight

Aviation support Components

Mobile Maintenance 3,

Maintenance Servicing 5 & 6,

Maintenance, Storage & Resave 1, 4 & 6,

Maintenance Annexe 1,

Mobile Air Torpedo Maintenance Unit 7,

No. 721 squadron Fleet Requirements Unit.

Aircraft type supported

Avenger Mk. I & II

Corsair Mk. II & IV

Firefly I

Hellcat Mk. I & II

Reliant I

Seafire III & L.III

Sea Otter I

Vengeance TT.IV

Commanding Officers

Captain A.N.C. Bingley 01 January 1945 to 17 July 1945

Commander W.S. Thomas (tmy COd) 17 July to 31 August 1945

Captain C.J. Blake 31 August 1945 to 10 November 1945

Related items

R.N.A.S. PONAM

History of the airfield and other information - part of the Fleet Air Arm Bases web site

The 'Jungle Echo the NABARON daily news sheet

The building of the US Navy airstrip on Ponam Island

Extracts from the cruise books of the 78th & 140th Naval Construction

Battallions

Reminiscences

Memories of those who served with MONAB IV

Leading

Air Fitter (Engines) Reg Veale.

Sub-Lieutenant (A) Peter Hyde

RNVR

Aircraft Mechanic (Airframes)

George Pickering

Telegraphist Kenneth Peterkin

Comments (0)