Mobile Naval Air Base No. VIII

Assembly and commissioning in the UK

Personnel and equipment for Mobile Naval Air Base VIII began to assemble on May 1st 1945 at RNAS Middle Wallop, Hampshire. It was to assemble as a Fighter Support MONAB, essentially no different from a standard MONAB which would support both fighters and torpedo bombers, its scale of issue excluded tools and spares for non-fighter aircraft types.

The unit was allocated the following components which were to cater for all fighter types in use by the RN in the Pacific theatre:

Mobile Maintenance unit (MM) No. 7 supporting Corsair Mk. II & IV, Firefly Mk. I, Seafire Mk. XV

Maintenance Servicing unit (MS) No. 13 supporting Corsair Mk. II & IV

Maintenance Servicing unit (MS) No. 14 supporting Seafire Mk. III & L.III

Maintenance, Storage & Reserve (MSR) No. 9 supporting Corsair Mk. II & IV, Firefly Mk. I, Seafire Mk. III & L.III

MONAB VIII was the first unit to be allowed to hold a trial run camp in order to help prepare the advance party for the initial tasks they would face in setting up the unit at its operational base. This trial camp took place at Cranford, not far from Middle Wallop between 8th - 11th June; the venture involved 12 Officers and 110 ratings. Whilst there, they erected Best Burkle Tents, Dorland Hangars and other equipment which required assembly before use. Opportunity was also taken to try to address some of the previously reported problems encountered by earlier MONABs.

Like the unit before it, MONAB VIII storing was done under the new system for the handling of unit stores; instead of all stores being delivered to the formation base to be checked, repacked and labelled ready for despatch overseas, everything was consigned directly to the port of embarkation from the store depots saving unnecessary transport and handling of store cases.

MONAB VIII Commissioned as an independent command bearing the ship's name HMS NABCATCHER on July 1st 1945. Captain V.N. Surtees DSO, in command.

Despatch overseas

By mid-July MONAB VIII and MSR 9 were ready for despatch to Australia; the unit’s motor transport and equipment had departed for Liverpool overnight on the 5th/ 6th of July, and the personnel travelled by train on the 23rd. On arrival the personnel embarked in the Troopship MALOJA, which sailed independently for Sydney on July 25th. The stores, equipment and vehicles were embarked in the Sea Transport EMPIRE CHIEFTAIN sailing on July 31st.

Both vessels were to make the passage via the Suez Canal, this was the first time a troopship had used this route, across the Indian Ocean to approach Australia from the west, all previous MONAB despatches had travelled via the Panama Canal. The MALOJA reached Colombo, Ceylon on August 14th, shortly after sailing the following day the Japanese surrender was announced; V-J Day was celebrated at sea. The MALOJA docked at Sydney on August 30th and the personnel disembarked to HMS GOLDEN HIND to await the allocation of an operational base, being accommodated under canvas at Warwick Racecourse during this period.

The decision was taken that as the war was now over MONAB VIII was not required for service in Australia; it had been planned that the MONAB should be installed at RAAF Amberley in Queensland but instead it would be sent to Hong Kong and be installed at Kai Tak airport to reopen the airfield and provide shore-based support for the elements of the British Pacific Fleet in the area.

After only five days at HMS GOLDEN HIND the advance party of MONAB VIII was embarked in the escort carrier SLINGER, which departed for Hong Kong on September 5th, calling at Brisbane and the Philippines on passage. The EMPIRE CHIEFTAIN had arrived in Sydney two days earlier on September 3rd and she sailed for Hong Kong on the 15th. MSR 9 was embarked in the escort carrier REAPER for passage to Hong Kong, sailing on September 28th.

Commissioned at RNAS Kai Tak, Hong Kong

Upon arriving in Hong Kong SLINGER was moored alongside at Kowloon and the advance party began unloading and transporting the MONAB personnel to Kai Tak to begin to set up the unit's temporary buildings. Kai Tak already had a naval presence before MONAB VIII arrived; the Avengers of 857 squadron had disembarked from the Fleet Carrier INDOMITABLE on august 30th during the liberation of the colony, they were joined by aircraft from two Light Fleet Carriers at the start of September. These were a detachment of 8 aircraft from 1851 (Corsair) squadron and 814 (Barracuda) squadron, part of the 15th Carrier Air Group (CAG) from VENERABLE on September 3rd, and 1850 (Corsair) and 812 (Barracuda) squadrons of the 13th CAG from VENGEANCE on the 8th.

MONAB VIII commissioned Kai Tak airfield as HMS NABCATCHER on September 26th. The EMPIRE CHIEFTAIN arrived at Hong Kong, on the 29th and work began to off load and transport all the unit’s stores, equipment and vehicles to Kai Tak. The Avengers of 857 squadron re-joined INDOMITABLE on the same day after a month ashore.

The RN set up at Kai Tak, the MONAB occupied the western half of the airfield. There are four Dorland hangars on the site. 1701 squadrons Sea Otters are parked to the left of the upper pair of hangars. MSR 9 with its two hangars is installed in the centre of the area by the runway intersection.

An airfield divided

MONAB VIII was to be operated along the same lines as the units in Australia, providing shore facilities for disembarked Squadrons and, eventually, to operate a Fleet Requirements Unit. However, the airfield was also claimed by the Royal Air Force and they also began operations from the field claiming Kai Tak for themselves and proclaimed it RAF Station Kai Tak - a point of contention as the Royal Navy also had plans for the station. It was decided that the station would be jointly occupied, with two sets of camp and maintenance areas. The airfield was split in half, the RAF occupied the eastern side with the pre-war airfield buildings while the RN had the western, undeveloped side, where the MONAB equipment was setup. The main RN maintenance area with four Dorland Hangars was established on hardstandings near the centre of the airfield with the workshops to the north, the accommodation site on the western edge of the field, and a dispersal area in the southwest corner. After many, sometimes nearly disastrous experiments at dual air traffic control, it was decided that the RAF should have sole control over Air Traffic Control.

Typhoon “Louise” struck the colony in the first week of October and caused widespread damage to Kai Tak, winds were so severe that the canvas covers were ripped of a newly erected Dorland Hangar, they were never found. Partly erected buildings were completely flattened and work on establishing the MONAB was set back several weeks.

Japanese prisoners were employed as labour on the station for many months, they were marched onto the airfield from Stanley prison each day and mustered by the Quarterdeck, they were then ordered to bow to the White Ensign as a mark of respect. Prisoner working parties repaired fences, dug ditches, moved aircraft in and out of hangars etc. The former Japanese officers were allowed to administer discipline when necessary, in many cases such disciplinary action would be taken in front of the mustered POWs before work commenced.

A small stock of reserve aircraft had been delivered to the station with MONAB VIII and Work had commenced on aircraft maintenance as soon as the equipment was available: 4 Corsairs, 4 Hellcat and 1 Avenger had been tested by the end of September. A dedicated Fighter support MONAB was no longer needed and NABCATCHER received a small number of Avenger and Barracuda Torpedo Bombers, and Hellcat Fighter Bombers in addition to the Corsair, Firefly and Seafire Fighters that they were initially task with supporting. Throughput increased with the arrival of MSR 9 to include 2 Avengers and 6 Barracudas in October and 7 Avengers and 1 Corsair in November. Many of these aircraft were ex-Forward Aircraft Pool (FAP) machines and It appears that some former FAP personnel had also been allocated to work with MSR 9; Air Engineering Officer Lieutenant (E). M.A.J.M. Hayward was one, an engineer and qualified pilot he undertook maintenance check test flights from Kai Tak. While carrying out a test flight on Corsair KD721 on November 25th the engine failed and he made a forced landing on the airfield (the machine was issued to 721 FRU in June 1946).

The next squadron to arrive on the station was 837 (Firefly) squadron which disembarked from GLORY on October 1st. REAPER arrived at Hong Kong on October 11th to deliver NSR 9 and ‘B’ Flight of 1701 (Sea Otter ASR) squadron. Beginning on the 12th detachments from 1846 (Corsair) and 827 (Barracuda) squadrons were disembarked from COLOSSUS, all had re-embarked by the 18th. On the 19th the aircraft of 15 CAG departed, re-embarking in VENERABLE.

1701 Squadron Headquarters was established at RNAS Kai Tak on November 1st 1945 under the command of Lt. (A) P.H. Woodham DSC RNVR; the squadron was reclassified as a second-line unit on this date. They were joined by 'A' flight on November 16th, which was delivered by the escort carrier STRIKER. The squadron now had a strength of 8 Sae Otter amphibians for Air Sea Rescue and communications duties.

On December 20th VENGEANCE’s 13th CAG re-embarked, 1850 having been reduced from 18 to 12 aircraft. With their departure only 1701 remained in residence on the station.

721 Fleet Requirements Unit arrives: In the New Year the station’s second resident squadron, 721 FRU arrived on January 11th on board the escort carrier SPEAKER; equipped with mix of Vengeance Target Tugs, Corsairs, Avengers, Seafires, and 1 Harvard they were to provide aircraft for radar calibration and gunnery exercises carried out by ships in the area. Three of the Vengeance Target Tugs were specially modified aircraft transferred from the Royal Australian Air Force for DDT spraying; they were employed by RN Mobile Malaria Hygiene Unit No. 1 when work began to eradicate the mosquito infestation from the colony in February 1946. Spraying commenced on Friday, February 15th, 1946. each of these spraying aircraft carried 320 gallons of DDT solution.

On March 1st 721 squadron lost two aircrew when Vengeance HB363 crashed; the aircraft went out of control in cloud and crashed into Junk Bay, 5 miles southeast of the station, killing Sub-Lt A.M. Brodie RNVR and POAM E. J. Desborough. There were two further flying incidents In April, both involving 721 aircraft; Vengeance A27-545, flown by Sub-Lt N.C. Burrage RNVR lost power on take-off on the 4th and d to abort, four days later Vengeance HB305, flown by Sub-Lt I. Houghton RNVR crashed on landing when its undercarriage collapsed. Also, in April 1701 squadron received a twin-engine Oxford, presumably adding communications duties to the squadron’s tasking.

There were two further incidents in May; on the 3rd Vengeance HB439, flown by Sub-Lt G. R. Harrison RNVR, suffered engine failure at 1,000ft over the airfield, it restarted at 300ft and a successful emergency landing was made. On the 23rd Vengeance FD303, flown by Sub-Lt J. Payne RNVR, swung off the runway on take-off.

721 squadron received several additional aircraft beginning in May; one RAAF Tiger Moth (A17-526), followed by several Corsair IVs in June which were issued from the reserve stock held on the station; this suggests an element of refresher flying training being added to the squadron’s duties.

Another severe typhoon caused widespread havoc in July, the RAF suffered most damage this time with five Dakotas, one of which was blown twenty yards away, and two visiting Sunderland Flying Boats being battered. 1701 received another aircraft in July, this time one RAAF Tiger Moth (A17-84), presumably for refresher flying training.

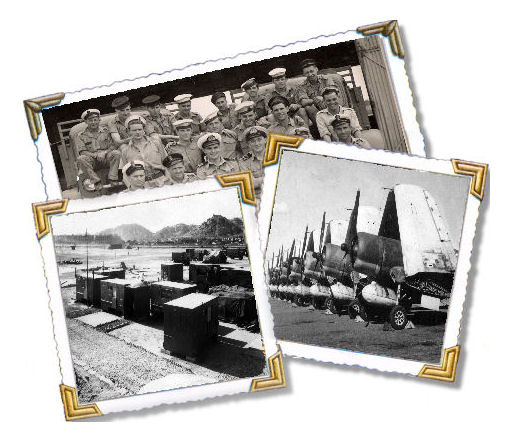

November 1945: Captain Surtees greets Admiral Fraser C-in-C BPF on his arrival at RNAS Kai Tak to inspect MONAB VIII.

Reduced to an R.N. Air Section

By the summer of 1946 the need for a full Naval Air Station at Kai Tak had ended and as part of the reduction in British forces in the area HMS NABCATCHER was to be downgraded to an R.N. Air Section. on August 27th 1946 MONAB VIII, HMS NABCATCHER ceased to be an independent command, it remained in place but its accounts were now held on the books of HMS TAMAR, the local naval base. On the same date 1701 squadron was disbanded at Kai Tak, it’s Sea Otters and one Tiger Moth were transferred to the strength of 721 FRU; the Sea otters forming 721 ASR flight.

Flying continued without incident into September when Vengeance A27-545, piloted by Sub-Lt G.R. Harrison RNVR, had a fire in the engine bay on the 24th (it is unclear if this was on the ground or in flight). On October 10th one of the FRUs Corsairs had an incident landing on, KD790 flown by Sub-Lt I. A. Hamilton RNVR stalled and a wing dropped striking the runway.

After nine months of second-line operations first -line disembarked squadrons returned on October 1st 1946 when the 16th CAG, 806 (Seafire F.XV) and 837 (Firefly F.I) Squadrons, disembarked from GLORY, they were to remain at Kai Tak until early November. 837 re-embarked their 12 Fireflies on the 4th, followed by the 12 Seafires of 806 on the 6th. While ashore one Seafire XV (SW786) flown by Lt, D.E.W. Aldous ran into the rudder of a parked Seafire while taxying to dispersal after landing on October 5th damaging the prop.

Command of NABCATCHER appears to have passed to Cdr (A) W.H.N. Martin on November 9th 1946. 721squadron received more new aircraft at the beginning of November, this time 2 Seafire XVs. Both of these had flying accidents within weeks of their arrival; SW854 flown by Sub-Lt M.H. Simpson RNVR made a heavy landing on November 11th and the undercarriage collapsed, on the 21st Sub-Lt N.G.B. Burrage RNVR in SW801 had his prop strike the runway on take-off. Sub-Lt Simpson had another incident on the 29th, this time in Vengeance A27-619 which suffered engine failure and he made a forced landing.

On November 27th the 24 aircraft of the 15th CAG arrived on the station, 802 (Seafire F.XV) and 814 (Firefly F.I) disembarking from VENERABLE. They were joined by GLORY’s 16th CAG on December 19th and all four squadrons were to remain ashore for Christmas and into the New Year.

By the end of the year 721 squadron had established three sub-flights; ‘A’ flight operating Vengeance and Seafire XVs and ‘B’ flight operating Corsair IVs, and an ASR flight operating Sea Otters. In December 1946 ‘B’ flight embarked its Corsairs in GLORY, possibly for Deck Landing Training (DLT).

The disembarked squadrons began to re-join their carriers in the New Year, first to leave was the 12 Fireflies of 814 on January 2nd, followed by the 12 Seafires of 802 on February 12th and finally 806 and 837 departed on February 14th; they were the last disembarked squadrons to be supported by HMS MABCATCHER. There was one recorded flying incident during this period; on January 25th; Firefly DK449 flown by LT. Cdr E.W. Pepper landed with the starboard undercarriage leg lock in the down position.

FRU flying continued in the spring of 1947; on March 11th Sub-Lt J.S. Kennedy failed to return from a local exercise north-east of Hong Kong in Seafire SW854, it is believed he baled out when the aircraft ran out of fuel off the China coast, but he was never found.

Paying Off

HMS NABCATCHER and MONAB VIII were paid off on April 1st 1947, the Royal Naval Air Section at Kai Tak re-commissioning the same day as HMS FLYCATCHER, the name formerly belonging to the MONAB formation station in the UK. The ship’s accounts remained with HMS TAMAR. This was the last of the 9 MONABs that were to see operational service overseas.

HMS 'NABCATCHER'

Function

Fighter support MONAB providing support for disembarked front line Squadrons, Air Sea Rescue Squadron (o.1701 Squadron), Fleet Requirements Unit (No. 721 squadron).

Aviation support Components

Mobile Maintenance (MM) 7

Maintenance Servicing (MS) 13 & 14

Maintenance, Storage & Resave (MSR) 9

Aircraft type supported

Avenger Mk. I & II *

Barracuda Mk. II*

Corsair Mk. II & IV

Firefly Mk. FR.I

Hellcat Mk. I & II*

Seafire Mk. III, L.III & XV

*Not planned support, included in revised planning upon

arrival in Sydney.

Commanding Officers

Captain V.N. Surtees D.S.O. 01 July 1945

Commander (A) W.H.N. Martin 09 November 1946 to 01 April 1947

Related items

R.N.A.S. Kai Tak History of the airfield and other information - part of the Fleet Air Arm Bases web site

Reminiscences

Memories of those who served with MONAB VIII

Commander A.W.F. Sutton

Petty

Officer Radio Mechanic Terry Rushton

Petty Officer Radio

Mechanic Charles Davidson

Leading Air Mechanic

(Electrical) Leslie Dickinson

Writer E.C. 'Mac' McCarthy

Comments (0)