Mobile Naval Air Base No. II

Assembly and commissioning in the UK

Personnel and equipment for Mobile Naval Air Base No. II began to assemble during early October 1944 at Royal Naval Air Station Ludham, Norfolk, the headquarters of the Mobile Naval Airfields Organisation (MNAO). The formation of MONAB II was to prove to be exceptionally difficult due to the fact that the duties of this unit were changed from that of a normal type A MONAB to that of a Receipt and Dispatch Unit shortly after formation began. This was a unit for which there was no scheme of complement laid down. The unit was to assemble with the standard MONAB elements, but the Maintenance and repair (Air) element received no Maintenance Servicing or Mobile Maintenance units, instead entirely new, and untested, components were substituted.

The following components were added to cater for all aircraft types in use by the RN in the Pacific theatre:

Aircraft Erection Unit

Aircraft Equipping & Modification Unit

Aircraft Storage Unit

The confusion caused by this role change was to be felt both at the formation station and in the operational area; the drafting office, based at R.N. Barracks, Lee-on-Solent, was not informed of the revised complement in sufficient time so the initial draft arrived at Ludham to find themselves surplus to requirements. A complement of 997 technical ratings for Maintenance, erecting and Equipping was finally decided upon by the planning staff and a new draft if replacement ratings was raised.

Split formation: A second immediate effect of the role change came with the increased size of the complement; a standard MONAB had an average complement of 550 personnel including officers, so MONAB II was nearly doubled in size. The formation station, Royal Naval Air Station Ludham could not accommodate such a large number as MONAB I was also present on the station and MONAB III was due to begin formation shortly. The solution was to accommodate some 600 ratings at HMS GOSLING R.N. Air Establishment Risley, over 100 miles away at Warrington, Lancashire.

This division of the complement made kitting up, checking of lists, and arranging short maintenance courses, and ultimately embarkation, unnecessarily complicated. To further compound an already complicated restructuring of the unit's assembly and formation period it was found that many of the ratings drafted were unfamiliar with the several types of aircraft which it was intended that MONAB II should handle; the formation time table made no allowance for rating familiarisation, unit sailing dates were pre-set so training outside of that set out in the formation programme was sacrificed. In addition to unprepared technical ratings, no adequate writer staff were drafted, ratings received were inexperienced; of three supplied for the workshop element, only one could type with any speed or accuracy.

Despite these problems MONAB II commissioned as an independent command on November 18th 1944, bearing the ship's name HMS 'NABBERLEY', Commander E.P.F. Atkinson in command.

Despatch overseas

By late-November the unit was ready for despatch overseas; all of the mobile units planned had been allocated to the support of the new British Pacific Fleet which was to begin operations in the South Western Pacific in early 1945. Australia was to be the rear echelon area for the fleet and a number of the MONABs were to be installed there.

The unit's stores & equipment were transported, overnight, to Gladstone Dock, Liverpool for embarkation on November. 20th; this operation was carried out by the unit’s own transport. However, the loading, of stores & equipment in the SS PERTHSHIRE, (LS 1974) did not occur until early December, she sailed On December 8th. The personnel of MONAB II did not embark for passage until December 22nd in company with elements from MONAB III and other units being shipped to Australia in the Troopship ATHLONE CASTLE, sailing from Liverpool on December 24th 1944.

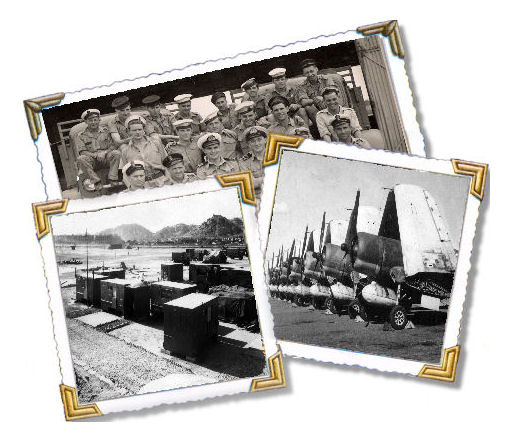

An advance party of MONAB II had been despatched to Australia and was in Sydney at the beginning of December. The party arrived at Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Station Bankstown, Sydney, early in the month to set up shop. Unloaded with the advance party were 16 crated aircraft, 8 Corsair IIs & 8 Martinet TT.Is collected from the RN Aircraft Depot at Cochin, S. India. These aircraft were to be assembled by the advance party, with RAAF assistance, and were to have been test flown by the time the main party arrived in the New Year. The first aircraft assembled, Corsair II JT537, was test flown on January 18th 1945. In early January two ferry loads of aircraft arrived to begin the build-up of reserve airframes prior to the arrival of the BPF in Sydney. These came from the UK and India onboard the escort carriers BATTLER and ATHELING.

The SS PERTHSHIRE arrived in Sydney on January 24th 1945 while the ATHLONE CASTLE arrived the following day; part of the ship's company proceeded directly to RAAF Bankstown, the remainder were temporarily accommodated under canvas at Warwick Farm, HMS GOLDEN HIND, while stores and equipment were unloaded and accommodation was sorted out.

Commissioned at RNAS Bankstown, New South Wales

Royal Australian Air Force Station Bankstown was transferred on loan to the RN on January 27th 1945; MONAB II began transporting stores & equipment to the station on this date. MONAB II commissioned Bankstown, as Royal Naval Air Station Bankstown, HMS NABBERLEY on January 29th 1945. Work began almost immediately, continuing assembling crated aircraft and carrying out pre-issue test flights.

RNAS Bankstown from 10.000 feet, taken on September 12th 1945..

The Receipt of Airframes: One of the most important departments on MONAB II was the Salvage Section. Under the charge of Lt. Cdr (A) P. E. Hind RNVR and Lt. (A) G. A. Pursall RNVR, grew into a team of four Chief Petty Officers, twenty Royal Marine drivers and about thirty naval airmen as mechanics come drivers. Originally tasked with the recovery of crashed aircraft, the occasional crashed aircraft was collected, but they became responsible for the movement of all aircraft and stores by road between the dockside and Bankstown.

Incoming airframes arrived at Pyrmont Dock in Sydney Harbour; this had been designated as a Fleet Air Arm dock and was run by the Australian Port Authorities in conjunction with the Royal Navy. Airframes and aero engines arrived by sea via several means, crated airframes and engines were delivered in the holds of transport ships or arrived as deck cargo on RN aircraft carriers. Preserved airframes were delivered by Escort Carriers, and, occasionally Fleet Carriers. Some of the Escort Carriers allocated to the BPF arrived on station with a full load of up to 70 aircraft plus crated engines and stores collected from RN Air Yards in the UK or India. Once off loaded all had to be transported to Bankstown by road convoy.

State law prohibited the towing of these aircraft through the city on their own wheels so special trailers known as ‘Spiders’ were employed to carry individual airframes in convoys of eight. Aero engines were loaded onto other flatbed trailers for transport. All were difficult loads which had to negotiate Sydney tram cables and tracks, these convoys were assisted by the New South Wales Police as they made their way across the city. When a carrier made a delivery there could be up to 70 airframes to move, this meant working night and day for about three days.

Once the replenishment and ferry carriers of the ‘Air train’ – the aviation support element of the Fleet Train , began operations Escort Carriers arrived about every ten days from the forward operating base in the Admiralty Islands to off load unserviceable aircraft and embark as many replacements as available for ferrying to the BPF Carriers engaged in operations against the Japanese.

Storage Unit surplus to requirements: By late February it became apparent that unexpected shortfalls in the aircraft production targets meant that the Mobile Storage element was redundant, all available replacement airframes were needed by the ‘Air Train’ so there were no reserve aircraft to process into storage. The situation was not seen as improving for the foreseeable future so the decision was taken to break up the Mobile Storage unit, sub dividing it to equip four new Maintenance Storage & Reserve units, MSR 3, 4, 7, & 8. Of these, MSR 3 & 4 were already assembling at Bankstown work having begun in early February. MSR 4 was allocated to operate with MONAB IV and an advance party was dispatched to its operational base, on Ponam Island, in the Admiralty Islands, on board the maintenance carrier HMS UNICORN; the second echelon of MSR 4 was embarked in HMS SPEAKER, arriving at Ponam Island on March 13th. MSR 3 had a different role to fulfil, it was divided into A & B sub units and embarked in the escort carrier STRIKER and UNICORN to support a Forward Aircraft Pool which was initially held onboard these carriers. MSR 7 & 8 were transferred to TAMY I upon its arrival in Brisbane in late March.

The first two replenishment carriers were prepared in early March; STRIKER (Flagship of 30th aircraft carrier squadron) spent the first week of March loading equipment, spares, airframes and passengers; on March 4th she embarked elements of MSR 3 from RNAS Bankstown, to provide additional capabilities and maintain a reserve pool of ready to issue airframes afloat. She sailed with a full ferry load of replacement aircraft, embarking as many as could be supplied from RNAS Bankstown for delivery to the forward base at Manus. After unloading she retained a replenishment load similar to that carried in SLINGER, but carried no operational squadron. She sailed for Manus on March 7th. SLINGER arrived off Sydney on February 26th and flew her squadron, 1845 NAS, ashore to RNAS Schofields, 3 unserviceable Corsairs were off loaded once alongside at Pyrmont Dock for repair at Bankstown. she sailed for the forward operating area on March 11th having embarked a replenishment load of 25 airframes from RNAS Bankstown; this load was made up of 10 Corsairs, 7 Hellcats, 3 Seafires, 1 Avenger and 4 Fireflies for issue to the fleet during replenishment periods; this load was carried in addition to her squadron which re-embarked once at sea.

Manpower shortages and other difficulties: After only a month of operating it had become apparent that the complement of non-technical ratings borne proved to be totally inadequate to meet demands of station duties; these elements had received no manpower increase in the revised complement. The shortfalls made it impossible to supply the necessary guards, working parties, galley hands etcetera without drawing on the technical personnel or loaning ratings, when available, from GOLDEN HIND, the R.N. Barracks, at Sydney. Shortages in manpower also applied to Cooks and Stewards; in MONAB II the average number of officers permanently borne was 85, as opposed to 36 for a standard MONAB. The already stretched drafting pool would be further strained after the war in Europe ended; plans to demobilise those who qualified by either age or length of service were eligible for release beginning on June 18th 1945 and meant that many experienced personnel could be lost and less experienced reliefs would be appointed or drafted to maintain manning level.

Being installed at an operational aerodrome none of the mobile Flying Control equipment supplied for MONAB II was used, however HF/DF, YG and JG Beacons and ground W/T installations were installed. MONAB II suffered from a serious shortage of M/T spares, spare parts issued in England were in the majority not required and those needed had to be purchased where possible from local sources.

Streamlined aircraft production: Once sufficient aircraft became available to permit a steady flow through the hangar’s attempts were made by the air engineering team to adopt industrial trade methods, namely to break down the jobs into small units so that a team could be trained very quickly to do a small job on each aircraft. This practice paid off, allowing for rapid gains in skill which enabled the process time of an aircraft on the hangar floor to be reduced considerably.

Co-operation between the Air engineering, Air Gunnery, Air Radio, and Air Electrical Officers had enabled work on an aircraft to be planned as a whole, enabling an aircraft to come out of a crate, enter one hangar and leave that hangar complete in all respects and ready for butt testing, compass swinging and test flight. However, plans to operate this scheme to its full extent were negated by ratings being drafted and by the intermittent arrival of aircraft resulting in varying output figures. The practice of sending secret equipment separate from the aircraft also caused considerable delay in bringing aircraft forward for service.

Over a period of several months’ aircraft production was refined into a 10-stage procedure;

(1) Aircraft arrives on station.

(2) To receipt park - loose equipment removed except when aircraft arc in sealed crates or Eronell (protective covering which embalmed aircraft for open storage or transport as deck cargo).

(3) Preparation of Servicing and Inspection Forms by the Inspection Section.

(4) Aircraft is allotted to a hangar for production - entry to the hanger was staggered in order to avoid having two aircraft reach the sane stage at the same time. A system approach ensured that Gunnery, Radio and Electrical sections worked on each aircraft in turn, and at stages where this work would not interfere with the Airframes and Engine ratings. Available modifications were incorporated during erection or inspection.

(5) Aircraft arrives at the end of hangar line for gun alignment, and final check by inspection team; during this final check an aircraft moves out of the hanger engine running.

(6) Move to Stop butts for gun firing and harmonisation.

(7) Move to Compass base - if an aircraft carries Radar it goes to Radar Base before the Stop butts, (Avengers were not Butt tested).

(8) Check Test Flight.

(9) To Storage - Category "B".

(10) Transferred to Storage - Category ''A" when loose equipment is available and the aircraft has been doped.

The output levels achieved fell well short of the production programme, partly due to a lack of airframes being delivered, and partly by the state in which crated or preserved airframes arrived on the station. Aircraft were received in varying states of equipment installation, some arriving completely installed, others partially installed and, in many instances, completely void of all equipment, in these cases equipment had been despatched separately and was unlikely to arrive with the airframe.

In the case of aircraft arriving with equipment installed, it was found that in the majority of cases all the equipment was in first class condition, requiring only a minimum of work to complete the testing and final installation of the aircraft. Any aircraft which were only partly installed (and in some cases only partly modified) caused serious delays owing to a lack of spare equipment. Considerable delay was also experienced due to aircraft arriving minus their entire radio equipment.

Test flying: The unit’s test flight was responsible for all ground and airborne testing of aircraft on leaving the production hangar. Ground crews conducted engine, electrical, radio and armament checks on aircraft in the storage park prior to the start of the test flight. There were up to 18 aircrew on the strength of the Test Flight, however there were more RAF pilot’s than RN, all under the command of Flight Lieutenant. Geoff Schaeffer RAF; he in turn reported to Commander (Flying), Lt. Cdr (P) G. R. Dence, RNVR who made the decisions about whether flights could be undertaken or cancelled based on local weather conditions. Flights were conducted every day, and only cancelled when cloud cover was too low. Once airborne every piece of equipment in the aircraft was checked - radio, guns, hydraulics, engine performance, and handling characteristics; depending on the type an observer and air gunner would be onboard. On completing a successful check test flight an aircraft was returned to the park for category B storage.

Squadron equipment issues: The personnel of 723 Squadron arrived from RNAS Nowra, MONAB I, on February 28th to commission as a Fleet Requirements Unit and receive their initial equipment issue of 8 Martinet TT.I and 8 Corsair II aircraft (the aircraft assembled by the advance party). The squadron was also temporarily issued with 2 Expediter Mk. I passenger aircraft in order to initiate communications flights in advance of the formation of 724 communications squadron which would begin operation in April. 723 carried out a short workup at RNAS Bankstown during March in preparation for beginning active duties, making regular flights to RNAS Nowra and its satellite airfield at Jervis Bay.

724 Squadron commissioned at Bankstown on April 10th, their Initial equipment was 2 Expediter Is (passed on from 723 Squadron) and 2 Anson Mk.I. 724 operated out of the civil airport at Mascot as the grass surface at Bankstown was unsuitable for the heavy twin engine aircraft. On completion of their formation and familiarisation at Bankstown 723 Squadron moved to RNAS Jervis Bay on May 1st to begin operations as a Fleet Requirements Unit.

First aircraft withdrawn from squadron service: On May 14th 1830 & 1833 (Corsair) squadrons disembarked from HMS ILLUSTRIOUS; both squadrons had their Corsair Mk. IIs withdrawn at Bankstown (her other squadron, 854 (Avenger) went to RNAS Nowra where their aircraft were retained). The carrier had been badly damaged by kamikaze planes on April 7th and had returned to Australia after receiving battle repairs in the forward area. 1833's personnel re-embarked in the carrier the same day; 1830 personnel joined them on May 24th when ILLUSTRIOUS sailed for passage to the UK.

A royal visit: On June 1st Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester, the Governor-General of Australia, toured the station. Whilst there he test fired a Browning 50 calibre aircraft machine gun at the test butts. The prince signed the gun's log book 'Henry' [but signed in the wrong place] the log was later raffled and was won by AM(O) 'Jimmy' Dixey.

On July 24th a detachment of Sea Otter Air sea Rescue amphibians of 'A' flightt 1701 squadron arrived from RNAS Maryborough, staying at Bankstown until August 7th.

The aircraft parking area at RNAS Bankstown 1945; three rows of new airframes, (minus wings, tail planes and engines) are lined up along the access road. Lines of packing crates containing the parts for the new airframes are arrange at right angles to these. Limes of ready for issue reserve aircraft are arranged in front of these.

Victory over Japan and the rundown to closure

Victory over Japan and the rundown to closure On August 15th the Japanese surrendered and VJ Day was celebrated at Bankstown. The men of HMS NABBERLEY marched in the Victory parade in Sydney, to mark VP Day on the 17th (In Australia the war's end was termed 'Victory in the Pacific' or VP day as opposed to Victory over Japan as it was known in Europe).

Work continued through August and September as the emphasis changed from assembling and issuing new aircraft to receiving and preparing surplus airframes for disposal. Aircraft withdrawn from disbanding squadrons at other RN air stations in Australia were gradually ferried to Bankstown , this vastly increased the numbers held in the aircraft park while their fate was decided. Some of the first to arrive were the Corsair Mk.IVs of 1834 & 1836 squadrons which began to arrive on the station from August 23rd for disposal; they had disembarked from the Fleet Carrier VICTORIOUS to RNAS Maryborough, MONAB VI where their aircraft had been withdrawn before the aircrew re-joined the ship.

By September, when aircraft production had ceased, 2,500 test flights had been made with only four major accidents (one complete loss and three major damages), three other accidents were due to the soft state of the airfield resulting in aircraft nosing up either after landing or whilst taxyng.

The Salvage/Movements section were busy at the end of August and early September as they moved large quantities of food, medical sand other essential supplies to Pyrmont Dock for loading onto ships preparing to sail for Hong Kong and Singapore to help re-establish the former British Colonies and repatriate POWs recently liberated from Japanese camps. Once this task was completed the section resumed aircraft movement duties, however they were now loading airframes for disposal at sea.

With the war now over the terms of the Lend-Lease agreement between Britain and the US required that remaining equipment should be returned or paid for, equipment that was destroyed however was written off. The Admiralty had been regularly disposing of severely damaged aircraft at sea during Pacific operations so the mass dumping of surplus airframes would see them ‘written off’. Once the carriers had completed their repatriation duties, many were tasked with ferrying deck loads out beyond the Great Barrier Reef and pushing them overboard.

Re-organisation: As part of a review of the naval air support in the Pacific theatre the Admiralty announced in October that four Mobile Units were to be disbanded in early November 1945, these were to be MONAB I, III, IV and VII; MONAB II, V & VI plus TAMY I would continue operations in support of fleet operations and the reception and disposal of aircraft arising from the disbandment of squadrons as the BPF began to reduce its size. As part of this downsizing operation MONAB V was to replace MONAB I at Nowra and MONAB VI would replace MONAB III at Schofields. MONAB VII personnel were to be redistributed to other units, many joining TAMY I.

'A' Flight of 1701 squadron arrived from RNAS Maryborough for a second, short period of detached duties on October 15th, returning to Maryborough on the 21st.

Paying Off

After months of processing the aircraft from the rapidly shrinking Fleet Air Arm in Australia and the South West Pacific the work of MONAB II was finally completed in March 1946. Her only squadron, 724 Communications squadron was relocated to RNAS Schofields to continue operations. MONAB II and HMS NABBERLEY paid off at Bankstown on March 31st 1946, and the station returned to RAAF control.

HMS 'NABBERLEY'

Function

Receipt & Despatch Unit.

Communications Squadron (No. 724 squadron)

Aviation support Components

Aircraft Erection Unit

Aircraft Equipping & Modification Unit

Aircraft Storage Unit

Aircraft type supported

Avenger Mk. I & II

Corsair Mk. II & IV

Expeditor II

Firefly I

Hellcat Mk. I & II

Martinet TT. I

Reliant I

Seafire III & L.III

Sea Otter I

Tiger Moth I

Vengeance TT.IV

Commanding Officers

Commander E.. P. F. Atkinson 18 Nov 1944 to 31 March 1946

Related items

R.N.A.E. Risley

R.N.A.S. Bankstown

History of the airfield and other information - part of the Fleet Air Arm Bases web site

Reminiscences

Memories of those who served with MONAB II

Lieutenant Gordon Pursall

Sub-Lieutenant Michael Price

Aircraft Artificer 4th Class (Electrical) Laurence

Russell

Leading Air Fitter (Engines) Bruce Robinson

Air Mechanic(Engines) Douglas Hooper

Comments (1)

My father, Henry Anderson served with MONABII, sailing out on the Athlone Castle from Liverpool. He was a technician, fitting and servicing radios and radars on the aircraft. He fell sick with TB while in Australia and spent some time in hospital and recuperating on Bondi Beach. He returned to UK in 1946, reaching the rank of PO2.